Building a Neighborhood

Take a walk around your block and look at the houses near you. Do any of them resemble the paper cutout houses? Look carefully at the type of construction materials, placement of windows and shapes of roofs to see what is similar or different from house to house. You can take photos or draw pictures to help help discover details that you may have never noticed in the past. Do the houses on your street share any similarities which help make the street feel like a "neighborhood"? Or is it the differences between them that make the street more interesting?

Once you've completed a few paper cutout houses, you can line them up to make a miniature city street. Use a big piece of paper or cardboard for a base. Draw sidewalks and streets on the base if you like. You can add other model houses in a similar scale, or even a few shoeboxes to represent simple shapes of buildings to create a mock-up of a city neighborhood.

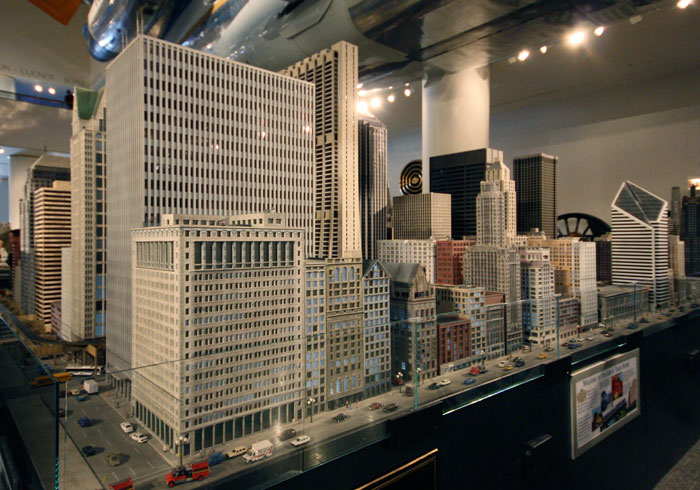

Most typical side streets in Chicago are 60 or 66 feet wide, which at 1:87 scale would be about 9 inches wide. Alleys that are 15 to 16 feet wide would be about 2 scale inches. Modeling a whole neighborhood at the relatively large 1:87 scale can quickly take up a lot of space. Many miniature buildings in model railroad layouts at this scale are not exact reproductions of real buildings but are "abridged" to capture the feel of the original buildings in a more compact size. The condensed skyscrapers in downtown Chicago in the Great Train Story model railroad at the Museum of Science and Industry are a good example. If you look closely you may notice that the miniatures have fewer columns of windows than the real structures to make them narrower, and that many of the less-memorable buildings have been edited out of this Michigan Avenue scene:

Urban planners and architects sometimes build models of whole neighborhoods or cities at a smaller scale to better see what effects new projects will have on a larger area. Nowadays computer-generated images may be used instead of physical models, but the idea is the same: to get a 3-dimensional idea of what a change to the city will look like in context. How do the buildings work together to make the look, feel and function of a neighborhood?

Shine a lamp or flashlight on your miniature street to simulate the shadows that the tallest buildings cast on their smaller neighbors. What are other ways that buildings can affect each other? What will happen if you switch the places of a few houses, change the sidewalks or parking spaces, or replace the smaller houses with tall shoeboxes? With a model you can simulate these changes to predict how they will affect the feel of the whole street.

This large wooden model has a variety of middle sections which can switched to see how different building designs and uses of the space will look and work in context with the surroundings:

Model of master plan for Rush Hospital by HDR Architecture, on view at Open House Chicago 2019

When looking at architectural models of new construction proposals, it is important to remember that our impressions of the finished building may be very different from our impressions of the model. Small things can be fascinating to examine closely. Looking down on well-crafted miniatures is like opening a window into a little fantasy world, evoking child-like feelings of wonder and delight. This charm can make any miniature building, even a poorly designed monstrosity, look exciting and fun. When the real building is complete, that charming sculptural design may end up looking like an oversized box out of scale to the humans on the sidewalks walking next to it.

To avoid such misperceptions, remember to look up as well as down on architectural models. Place a camera or your phone carefully down close to the miniature to get a scale eye-level view for a better impression of what it might be like to experience the real building when it is built. The materials and finish of the real building may not be accurately depicted in the model, but the massing and proportions allow us to imagine how this space might appear in real life.

The vernacular structures depicted in these scale models were built at a time before car ownership became common. Their proportions and decorative details were meant to appeal to pedestrians walking by as much as for the use of the inhabitants. After World War II, the automobile leapfrogged development to wide highways beyond the city limits. The longer braking distance of speeding cars fostered a new vernacular architecture to be seen at a greater distance, of roadside businesses encircled by parking lots and ranch homes set on wide lawns.

Real estate agents and urban converts now recognize that the pedestrian scale of older cities can provide many of the same charms that attract tourists to vacation in tourist towns around the world. Walkable neighborhoods are finding a renewed popularity. Walkability is measured by how many daily needs, such as work, school, shopping and entertainment, can be reached within walking distance. It can also give a measure of the density and mix of uses that make urban places vibrant and interesting.

The increased demand for urban housing can diminish that density and vibrancy of the city if rising rents mean only wealthy people can live in walkable neighborhoods and older apartments are replaced by luxury condos. For the sake of the urban "soul of the city" that its residents value, it is important to preserve the humble vernacular architecture of the neighborhood that provides affordable housing and a historical backdrop for pedestrians to contemplate as they walk by.

Find out more

Cities in Miniature - Miniature visits to scale model cities around the world

How Walk Score Works - How does your street rate?

In Depth

The Experience of Place, by Tony Hiss - A compelling exploration of how the structure of urban spaces affects our experiences in them

Traditional Development is Not Retro. It's Timeless. - One of many Strong Towns articles and resources supporting walkable development